By Edward Chisanga and Caesar Cheelo

Economic resilience

Perhaps too early to be felt fully today, in the coming years, the negative impact of Covid19 on the Zambian economy will be too ghastly to contemplate. When countries are confronted with such unfriendly disasters which prove uncongenial to the wellbeing of society, they look to the private sector to lead a protracted war, with Government’s support, against the external invader. We deliberately use the term ‘lead’ to descript the expected private sector response and install it in the private sector because that is the economic agent that possesses or should possess the economic tools for driving growth and prosperity.

Some argue that economic resilience is built through factors such as trade liberalization and globalization. Yes, we agree but only bearing in mind that a country has products to export or to import. Otherwise, the single most important factor that builds economic resilience rests in the supply side of any economy. Zambia’s private sector problem, in particular why it cannot amply respond to any external threat such as Covid19 (and silver lining opportunities therein), is largely that its supply side is not only weak, but also falling towards the abyss with each passing year. Some argue that it is actually already in the dark abyss while others would like us to believe that it is getting stronger.

Soon after independence in 1964, a deliberate campaign to diversify the Zambian economy was launched by the first leadership and it led to remarkable building of the manufacturing sector, which produced a variety of our own commodities like cooking oil and other agro-processed goods, batteries, processed drinks, clothes and school uniforms, bicycles and even the assembly of FIAT and Land Rover vehicles. Had we continued from there and continued to empower the private sector to run this sector, perhaps by now the economy might be somewhere close to where Viet Nam is. We reiterate what we have said before elsewhere that Viet Nam has overtaken Africa, including South Africa, in terms of world exports of manufactured goods.

Economic growth and Covid19 effects

Zambia’s economic problem is of course a product of policy choices of the political leadership. But more importantly, it is a result of a private sector that never grew to maturity, neither quantitatively nor qualitatively. Although some public opinion would have us believe that economic development is driven by politics and therefore politicians, the truth is, the real engine of development is the private sector. It is the private sector that creates jobs, and generates wealth and exports; even though in Zambia the perception seemingly is that that is the role of Government, under the local adage ‘boma iyanganepo’ (‘the Government should look into it’).

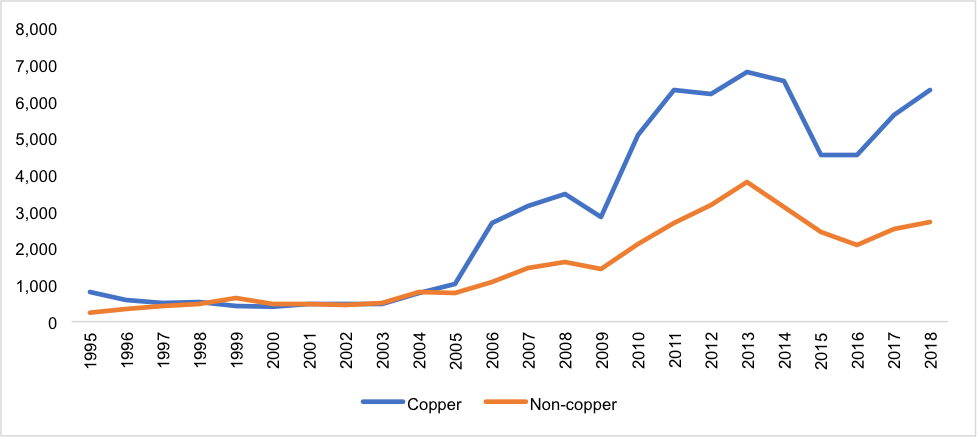

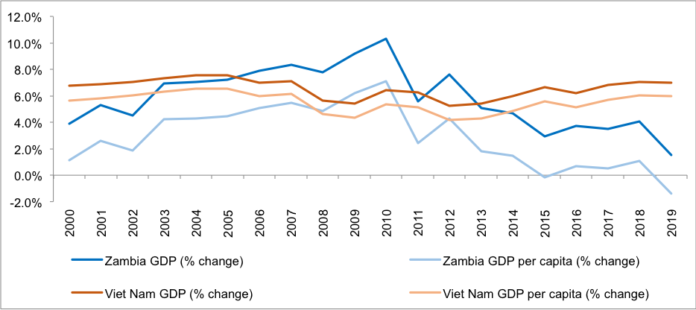

In recent times, Zambia’s economic growth has been eroding away, largely because the country’s private sector is not only low on domestic productive capacity but is also uncompetitive globally and even regionally. There are periods when the economy has grown impressively, such as from 2000-2010, with GDP growth reaching unprecedented level of 10.3% in 2010 (ahead of Viet Nam’s 6.4% growth in the same year) as Figure 1 below shows.

But the economic indicator often forgotten and less popular to the common man and woman is the growth rate per capita, which crudely reflects the average income of individual households. In the last ten years, (2010-2019), both GDP and per capita growths in Zambia – in contrast with the steady trends of Viet Nam – have been declining at an unprecedented level; GDP, from 10.3% in 2010 to about 1.5% in 2019; and per capita GDP, from 7.1 to about minus 1.4% according to UNCTADstat estimates. This has been largely due to the decelerating robustness and in many instances deterioration of the private sector. Thus, the real growth of the economy or its per capita growth in a given year, say 2019, cannot and should not be judged based on that particular year alone. We have to take into account the economic fortunes or turbulence and underlying policies and business environment of the last ten years. This is what underpins the trend in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Twenty-year tends in Viet Nam and Zambia’s economic growth in percentages

Source: constructed from Unctadstat (https://unctadstat.unctad.org/)

Moreover, not reflected in Figure 1 is that with the effects of the Covid19 pandemic on the Zambian economy, real GDP growth is expected to contract by 4.2% or more by the end of 2020. Before the Covid19 problem, the economy was already in decline and so with the pandemic, all remaining elements of private sector resilience to sustain productivity and growth are likely to erode away. Productivity growth in many companies is likely to weaken, companies likely closed and jobs likely lost as the private sector lays-off workers due to low consumption demand and subdued economic activity. Zambia’s private sector simply does not possess the required resilience to withstand strong exogenous shocks like the Covid19 pandemic.

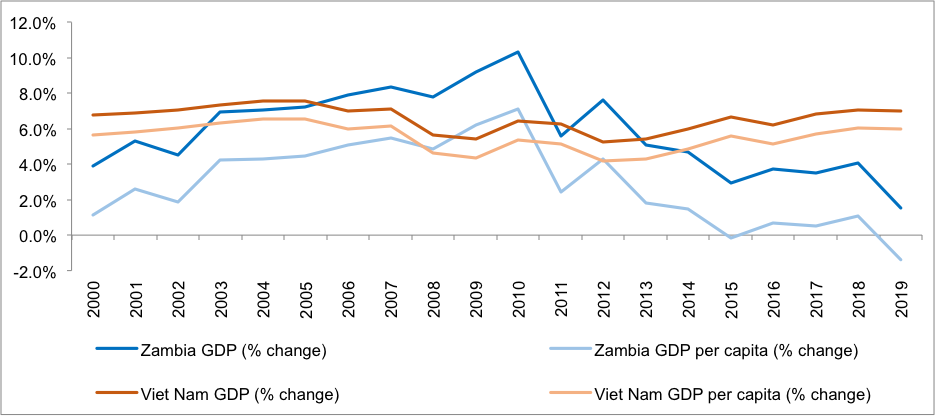

Exports and their contribution to household wellbeing

Without a strong production and supply base, Zambia cannot diversify or add value to exports. And, it is not trade liberalization or opening the country to imports that builds resilience. Currently, Zambia’s exports are divided between two main owners. One is the copper owner, who, in the country’s total exports of $9.0 billion to the world accounted for 70% in 2018, leaving the non-copper owner to account for only 30% or only $3.0 billion. In other words, excluding the copper private sector, it means that the non-copper Zambian private sector’s total exports amount to only $3.0 billion per year on average and when this is divided by Zambia’s population of 17 million, it means each Zambian essentially earns the equivalent of less than $200 per year or less than $20 per month in exports. That private sector contribution to household economic and social wellbeing is not worth writing home about. Neither is this the kind of private sector that can contribute to economic resilience to ward off the devastating negative impact of Covid19 and other external or local disasters.

Watch too that the trend of non-copper exports shows a downturn as Figure 2 below shows. Bear in mind as well that once upon a time, in the brief period 1999-2001, non-copper export products had dominated exports over copper. What happened? Why did the private sector fail to continuously replace copper with non-copper exports in its export profile?

Figure 2: Trend in exports of non-copper products in $ Millions

Source: Unctadstat

Export information provided by Zambia on the COMTRADE database shows that out of the total exports of $9.0 billion across all products, copper (unrefined copper plus cathodes together) amount to $6.0 billion, which accounts for 66%. Thus, a key question is: which products, among those the top twelve export commodities from Zambia come from the local private sector other than the mining sector? Moreover, Zambia’s top fourteen non-copper export products total only about $690 million, accounting for only 8% of total exports of all products. By all standards, these export values are simply too low and far from global competitiveness. Oil cake, the highest non-copper export earner in 2018, fetched only $68 million while the rest each fetched less than that. One is forced to ask the question: What will the local private sector in Zambia competitively export under the forthcoming Africa Continental Free Trade Area, particularly considering the competition with countries like South Africa, Egypt, Morocco, Tunisia, Kenya and Cote D’Ivoire?

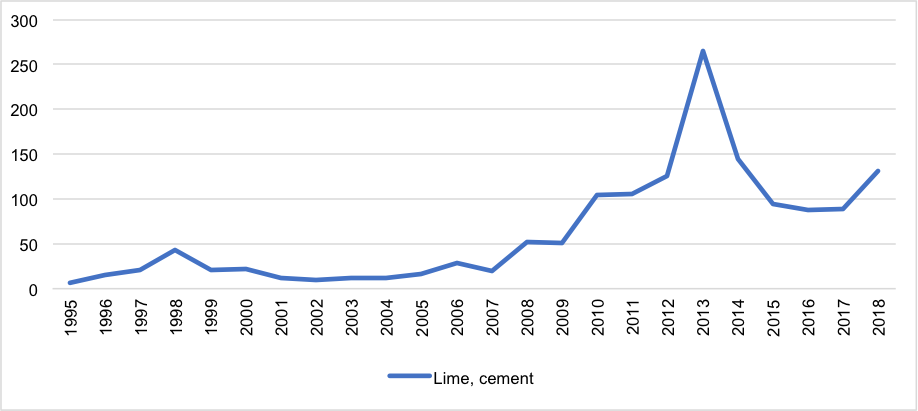

In Figure 3 below, we show lime/cement as an example of one of Zambia’s top export products ranked number five in 2018 according to UNCTADstat data. The last twenty-year trend shows that this product is not reliable, like other basic commodities, copper included. The period 1995-2008 shows flat export values of less than $50million annually. And, while the trend improved sharply in 2013, reaching $265million, the highest peak, that could not continue. Instead, export values shrank to less than $150 million in 2018. That is why we think that the better economic model would have been for the country to concentrate its development program on alleviating supply-side constraints rather than the demand side problems. Zambia would have made a significant difference by using an industrialization-driven trade liberalization reform also given that free export markets are abundant under the existing trade preferences of developed and even developing countries.

With the Covid19 pandemic reducing economic activity and demand for goods and services globally, and being overly-dependent on trade with the rest of the world, Zambia’s exports are likely to fall, further weakening an already fairly low capacity private sector. Already, an immediate effect of the Covid19 associated trade, transit and travel restriction was an average export reduction of 4.9% per month (14.8% cumulatively) between February and April 2020.

Figure 3: Trend of Lime/cement’s export to the world in $ millions

Conclusion

From this piece, different readers will take different perceptions of Zambia’s private sector and will draw different conclusions. To us, what is clear is that the domestic, non-copper private sector is almost non-existent, at least in terms of trade and contribution to economic resilience. To build local private sector productive capacity and value-added competitive export competences will require more investment in fundamentals for long-term growth. These are listed by Dani Rodrik, as ‘human resources, physical infrastructure, macroeconomic stability and the rule of law,’ and we add, local and foreign direct investment and technology transfer in particular in the manufacturing sector, all known by Zambia’s development practitioners.

Current local private sector investment, including its potential for growth, is simply too low. With the advent of the Covid19 pandemic, private sector productivity capacities, resilience and GDP growth contributions have all deteriorated markedly and as we argued earlier, Zambia’s private sector is ultimately found with insufficient resilience to weather the storm of the Covid19 pandemic. Urgent Covid19-smart mitigation measures for the local private sector will be essential if the economy is to rebound from its current slum and restore positive growth.

The private sector could learn from the export-led industrial development model in East Asia where Japan took the lead followed by Asian tigers and further by other ASEAN countries. Japanese FDI in the region among others placed a targeted role in building local productive capabilities as Japanese supply chains expanded in the region. Perhaps an implication is that Zambia and SADC sub-region should seek to follow that model with South Africa taking the lead and expand, deepen and solidify intra-SADC value chains and networks so as to build local capacities and resilience in Zambia.

It is not enough to simply make public statements like a recent one by Minister of Foreign Affairs, “Industrialization remains at the core of the SADC integration agenda” when data shows that the share of Zambia’s intra-SADC exports of manufactured goods in total is eroding, for example, from 53% in 1997 or in recent years from 46% in 2014 to 37% in 2018. Argue Dani Rodrik and Margaret McMillan, “The larger the share of natural resources in exports, the smaller the scope of productivity-enhancing structural change. The key here is that minerals and natural resources do not generate much employment, unlike manufacturing industries and related services.” Zambia’s intra-SADC exports of primary commodities account for 63% of total. Numbers also show that in 1990, within SADC states, Zambia’s share of 30% manufacturing value added in GDP ranked number two after Eswatini but in 2018, this ranking dropped to number seventeen with 6%. In absolute value, Zambia’s manufacturing value added in the economy is valued less than $2 billion compared to Tanzania’s $5 billion. Over the long-term, a well-developed private sector such as those in Asia will be able to respond more effectively to exogenous Shocks.

A simple answer to your question is yes. I have business in private sector and can vouch in saying that the government has ensured a resilient economic environment.

A simple answer to your question is yes. I have business in private sector and can vouch in saying that the government has ensured a resilient economic environment. Kaizar

I hope they paid to publish those graphs. It is worst of time, nobody reads that, including idyots like, wife abuser Lusambo. Ask Lusambo what it understand in those %s.

After HH had described the state of the economy under MMD with all the technical jarg, Sata comes and says, ‘Now let me tell you politics.’ He went on to win the next election. This is what we lack. People who can limn issues at hand in a way that the man in the street can understand. In developed countries, whenever the budget is announced pundits gather ordinary people from all walks of life and explain to them how they will be affected. It is obvious that Covid 19 will have a negative effect on the national economy. Everyone knows that. Tell the hairdresser, the charcoal burner, the carpenter, the street vendor etc how they will be affected. That is what we need.

Comments are closed.